Traveling east on Route 60, it’s impossible to miss the true beauty of southern Wisconsin. The gently rolling cropland and pastures, dotted with old barns, are occasionally broken up by the main streets of small towns. The region seamlessly mixes the past with the present.

At the crossroads with U.S. Route 45 in Washington County, the Village of Jackson encapsulates the mixing that many of these communities are experiencing. Over the past 30 years, the Village has more than doubled in size. The growth has converted much of the adjacent farmland into subdivisions for families.

It was a fitting place for the local producer-led group Cedar Creek Farmers to organize and co-host the Cedar Creek Community Connection last September, a first-of-its-kind public event to showcase what urban and rural folks can do to protect water quality.

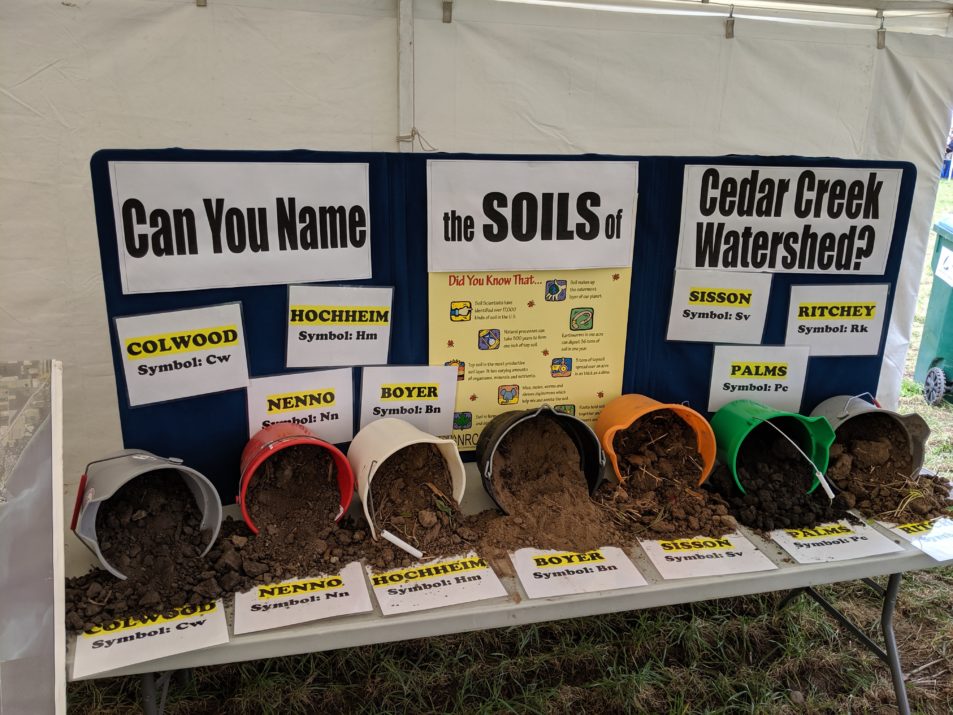

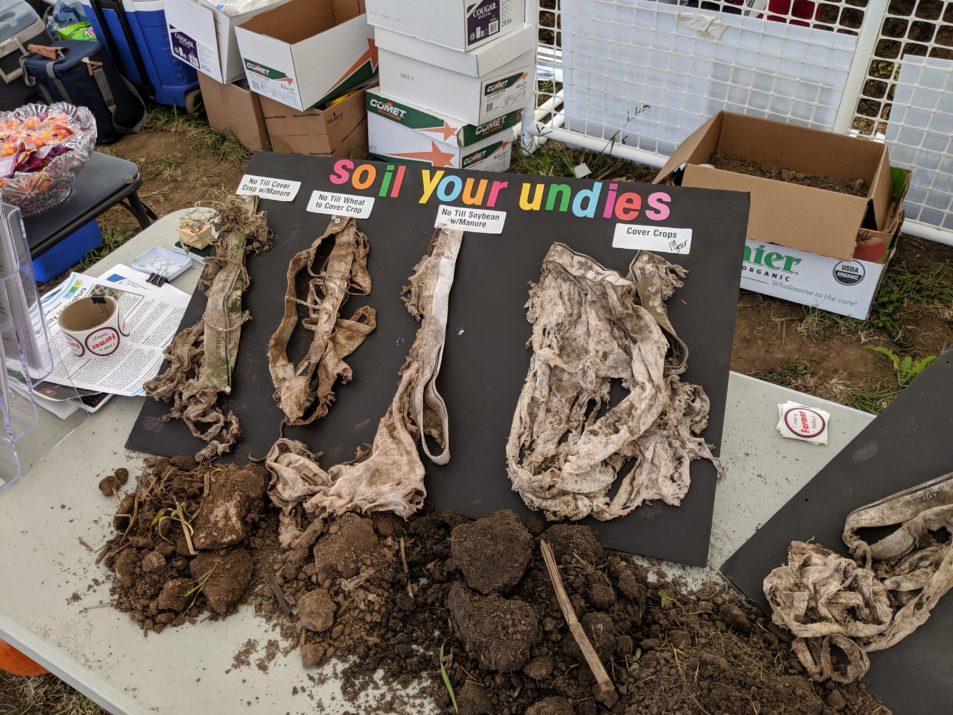

The event was divided into two adjacent tents, one for urban and one for rural. The urban half focused on the Village’s wastewater treatment system and educated attendees about stormwater runoff. The rural tent hosted a variety of educational stations, including a soil pit, soil sampling station, and most notably the Soil Your Undies display, which showed how powerful microorganisms in the soil are in breaking down and converting cotton underwear into nutrients.

For the roughly 100 families at the event, this was their first opportunity to learn how both municipalities and farmers protect water quality through interactive displays and direct conversations. For the Cedar Creek Farmers, this was an important moment to spread awareness about soil health and how sustainable farming benefits the community as well as the crops.

“It was very important for the farmers to be able to tell their story,” said Stephanie Egner, Washington County Conservation Technician. “This was a moment to show both the urban and non-agricultural public what farmers can do to improve their communities.

Helping the public better understand the connection between land use and water quality has been a particular concern for communities big and small across Wisconsin. Discussions about harmful contaminants in public drinking water have been elevated since Governor Tony Evers declared 2019 the Year of Clean Drinking Water and the legislature launched the Speaker’s Task Force on Water Quality.

For the Washington County Land and Water Conservation Division (LWCD) and the Cedar Creek Farmers, they knew that this was a moment to exemplify how farmers are making a positive difference in the watershed with conservation practices like cover crops and no-tillage.

“Cover crops really amplify the biology and the strength of

the soil,” said Ross Bishop, local farmer and member of the Cedar Creek

Farmers. “No-till by itself is great and I have no-tilled for 25 years. On top

of that, I’ve been using cover crops for over 10 years. And in the last five

years, I’ve seen the cover crops make these yields really shine. It’s all about

building and increasing the fertility of the soil and the cover crops have

really helped me get up between 4-4.5% organic matter in the soil.”

Building organic matter is fundamental to the soil health movement. Organic matter, or the decomposed humus from organic materials, provides a huge nutrient supply to crops. According to the Noble Research Institute, 1% of organic matter releases 20-30 pounds of nitrogen every year.

Importantly for Wisconsin fields, organic matter help decrease erosion and improve water infiltration. Organic matter acts like a sponge, with the ability to absorb and hold up to 90% of its weight in water that is then available to plants.

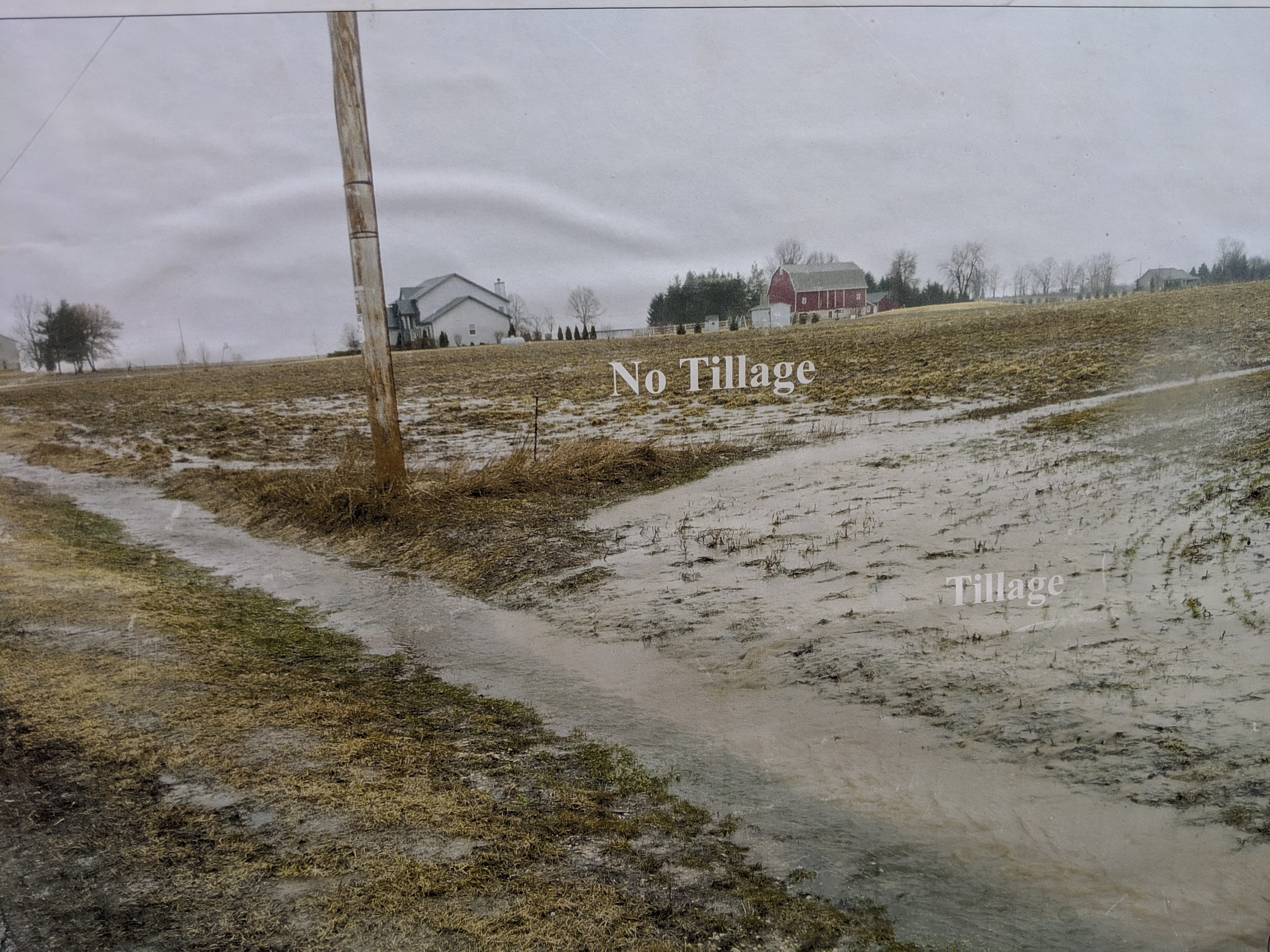

This has been one of the critical factors for farmers over the past five years as Wisconsin experiences unprecedented storms and flooding events. Conservation practices like cover crops and no-till have helped farmers manage much larger storm events, as the fields better absorb rain water and hold the soil in place. In the short term, this can save operations a lot of time and money as the fields dry out faster, less soil is displaced, and the crops need less inputs.

“Our group has had success helping other farmers in the watershed understand that even a paper-thin amount of soil loss every year is incredibly expensive for an operation,” said Bishop. “Being able to have visual exhibit that show the power of healthy soils really helps people make the connection.”

The Cedar Creek Farmers is a relatively new group that formed in 2016. It began by Washington County LWCD reaching out to 10 farmers who they had worked with in the past. These farmers were early adopters – farmers who were experimenting with conservation practices, like reduced or no-till and cover crops, before the soil health movement become popular. The conservation department then invited them to a local coffee shop to pitch the program and see what they thought.

“After we explained the producer-led program and that there was new grant funding available to support soil health practices, these guys said right from the start – ‘we’re already doing this and we already feel like we’ve been successful at adopting these practices using NRCS’s EQIP funds. Let’s use this program to give funds to other farmers in the watershed for them to try it,’” recalled Paul Sebo, Washington County Conservationist.

“These guys weren’t after the money for themselves. They believe that these practices have benefitted their operations and continue to make a positive difference in water quality, so let’s try to get more farmers to do it,” continued Sebo. “It is as an easy way to offset the costs that come with experimenting with new practices in a very simple process. The one-page contract is straightforward and the hope was that if we get some other farmers to try out these practices and they want to do more, we will help them secure more funds for long-term adoption.”

“I think our group, although we’re small, are helping other farmers take the leap to try what we’re talking about,” said Bishop. “Just this past year, I was able to work with a 70-year-old farmer to help him do no-till soybeans on cover crops for the first time. Although he wasn’t someone that would have been inclined to try this, after we did it, he’s very pleased with how it turned out.”

Diversity was another important detail to the success of the Cedar Creek Farmers. The group intentionally included grain, dairy, beef, and vegetable farmers to bring a well-rounded discussion about how to implement soil health practices correctly for different producers. Additionally, a diverse age of farmers created a unique mix of experience and enthusiasm.

“We have guys in the group in their early twenties and guys into their sixties,” said Egner. “The group is led by farmers like Ross Bishop, who have been farming for 25 years, that are mentoring and teaching the younger generation. It’s really a special opportunity for these experienced farmers to lead by example, and what better way to get the younger farmers involved than to say ‘hey, come be a part of something – this is going to be great for you.’”

“The new generation is very open to trying soil health practices,” noted Bishop. “It’s much harder to break old habits than teach new ones.”

Within the farming community, passing down the generational knowledge within families is a deep tradition. Many farmers first learn how to farm from their parents, who learned from their parents, and so forth.

Unfortunately, the inherited knowledge of farming is lessening as farmland continues to consolidate and medium-size family farms shut their doors. Although there are many factors that contribute to this national trend, one stands out – the average age of farmers is slowly increasing, as less young people are farming full time.

“People don’t farm forever. Land is going to get passed down to the next generation and it’s really important for them to access the knowledge that the older guys have and to learn how to improve their soil health and water quality through conservation practices,” said Egner.